The False Freedom of the Female Voice

CW: sexism; mentions of sexual assault and intimate partner violence; sexist language.

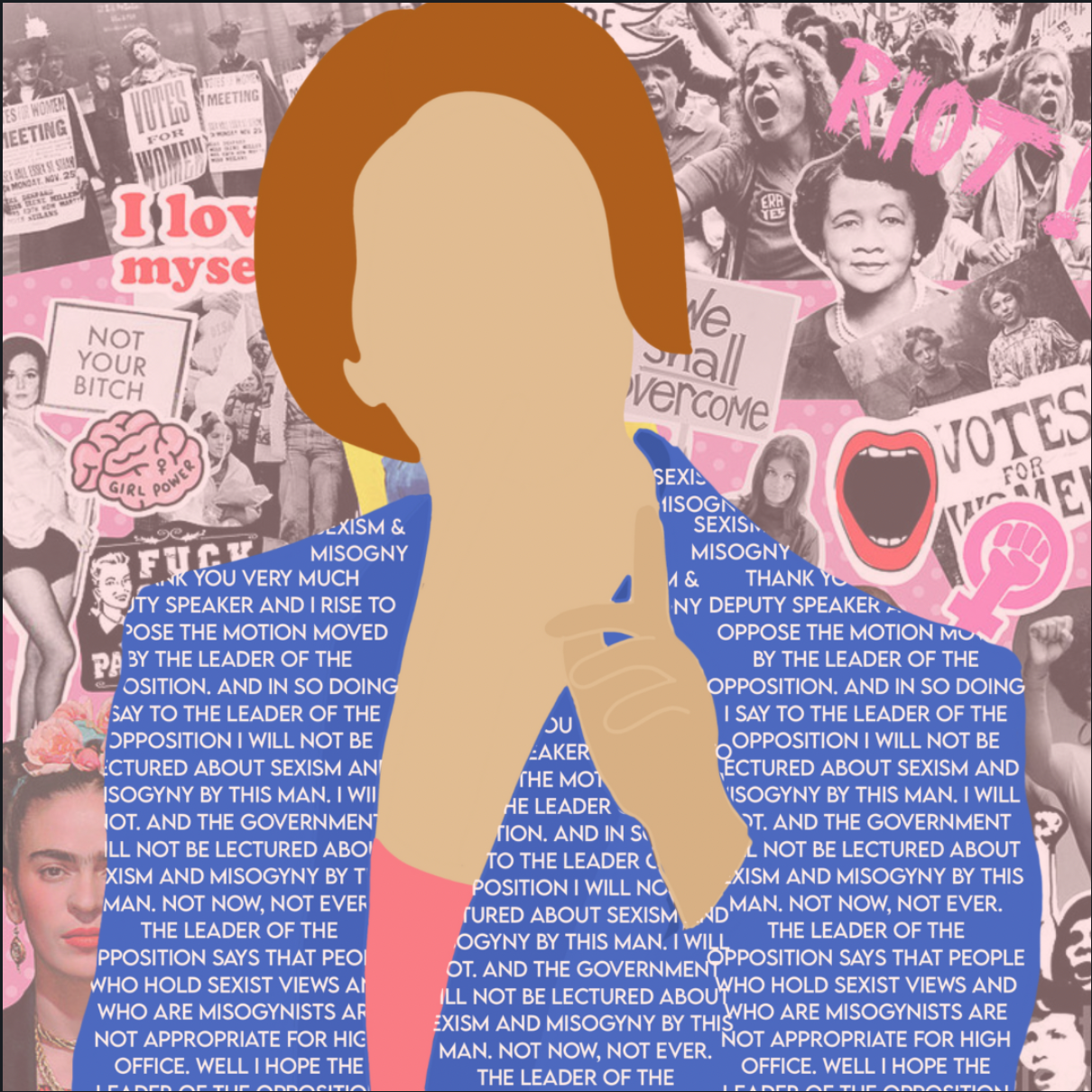

"And then of course, I was offended too by the sexism, by the misogyny of the Leader of the Opposition catcalling across this table at me as I sit here as Prime Minister … I was offended when the Leader of the Opposition went outside in the front of Parliament and stood next to a sign that said, “Ditch the witch”. I was offended when the Leader of the Opposition stood next to a sign that described me as a man's bitch … Misogyny, sexism, everyday from this Leader of the Opposition."

Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s ‘Misogyny speech’ in 2012 was a striking response to the political vitriol that haunted her leadership. Her time as Prime Minister was characterised by sexual denigration and abuse that went further than routine political satire—her public identity was epitomised by misogynistic insults like bitch, barren, hag, slut and cow rather than by reference to her Prime Ministership.

The offensive language which tainted Julia Gillard’s leadership was nothing new, and I’m sure many would argue that it was nothing to be apologised for. Australians have long been painted as loutish and loud, with stereotypical Australian culture rooted in insult and invective. We’ve staunchly defended our blunt and offensive language, claiming it as an element of our right to free political expression. Gillard’s critics argued that the abuse she suffered was part and parcel of her position as Prime Minister—perhaps she was just too ‘fragile’ for the realm of junkyard dog politics.

The Australian Constitution contains no explicit right to ‘free speech’. Instead, our freedom of political communication has been extrapolated from the requirement in sections 7 and 24 that our government be representative. Australian courts have made it clear that Parliament cannot regulate the civility of political communication; to do so would prevent citizens from participating fully in our representative democracy.

But here emerges something that may be inherent in the scope of the implied freedom of political communication in Australia—binary conceptions of gender.

Consider the idea of the ‘male’ versus ‘female’ voice; that styles of communication follow a gender binary between cisgender men and women; that when authoritative women* speak, they speak for all women; and that the male voice is the most valuable.

To be clear, there cannot be a singular ‘female’ voice. Nor a singular ‘male’ voice, for that matter. To claim the existence of either is to ignore the complexities of gender identity and the nuanced intersections between gender and one’s experience as a public being. But a feminist critique of the freedom of political communication in Australia suggests that the law still operates according to a gender binary—one where traditionally ‘masculine’ styles of communication are valued.

The problem is that it’s easier to dismiss women who speak out on issues concerning their public identity when we accept the existence of a singular ‘female’ voice. I’ve been accused of ‘playing the gender card’ when recounting my own experiences of sexism more times than I can count. I’ve often felt that my arguments have been deemed invalid and unworthy of proper consideration when they challenge the social stereotypes of gender which predict what women should say and believe. Women in positions of power are not immune from similar criticism. When we consider that positions of public authority in Australia have almost always been held by men, it’s unsurprising that groups of authoritative women speaking together on important political and social issues still remains a novelty.

Unlike the ‘female voice’, the stereotypical ‘male voice’ is the voice of civic beings participating fully and freely in public debate. When men speak about gender, society, and civility, they run very little risk of being caricatured as emotional and unreasonable. There are few allegations of intellectual weakness or fragility within the rigours of public life, and little risk of their losing the opportunity to speak in the first place. The dominance of ‘male’ perspectives in political discourse has clear historical roots—indeed, men developed the idea of civility and free speech alongside the development of the Constitution in the late 19th century. What they understood to be tolerable in the realm of public discourse in 1901 fell within the realm of speech protected by the Constitution, and this pattern appears to have continued ever since.

The implied freedom of political communication operates within a societal context which sees offensive language and incivility as inherently ‘masculine’, and vehemently protected by men (especially those on the High Court bench). The effect of this masculinisation of speech in the context of feminist legal theory is that blunt, offensive, and assertive styles of communication are valued. When women speak in similar tones, they are often discounted as abrasive and unreasonable.

When we dismiss the unique and diverse voices of women, we accept male perspectives as the benchmark of reasonableness. This leads to the acceptance of an objective version of reality which ignores the diversity of female perspectives in Australia. We can see how these ‘realities’ have permeated legal and political discourse. They include the idea that victim-survivors lie in sexual assault cases; that people who experience intimate partner violence and don't leave the relationship have ‘chosen’ to be abused; and that people who are offended by sexism and misogyny are too delicate to survive the harshness of public life.

Bringing the voices of women* into political conversations and affording them the same respect and value as the perspectives of men, is important to displace these 'realities'. We must remember too that, when a ‘woman’s voice’ manages to infiltrate mainstream political discourse, it can often still be traced back to structures of privilege which continue to favour white, cisgender and able-bodied women. We must focus specifically on amplifying and celebrating the voices of women which have been historically ignored. We must also acknowledge that political discourse can be robust and open without resorting to gendered vilification—while insult and invective may be protected aspects of political communication in Australia, I would hope that sexism and misogyny are not.

By Sophie Aboud

[This piece was originally written as an assessment item for a law elective at the Australian National University. It has been edited for length and clarity.]